Prologue: Zarvan by the River

Zarvan stood by a river older than any kingdom, where reeds bent like bowed priests and waters whispered of life—and of waterborne diseases, the hidden sicknesses that have followed rivers as long as memory itself. The air was damp, yet alive, as if every droplet still remembered the footsteps of those who had come before. To Zarvan, water was never just water. It was memory, flowing without pause, binding the fate of empires and the breath of children alike.

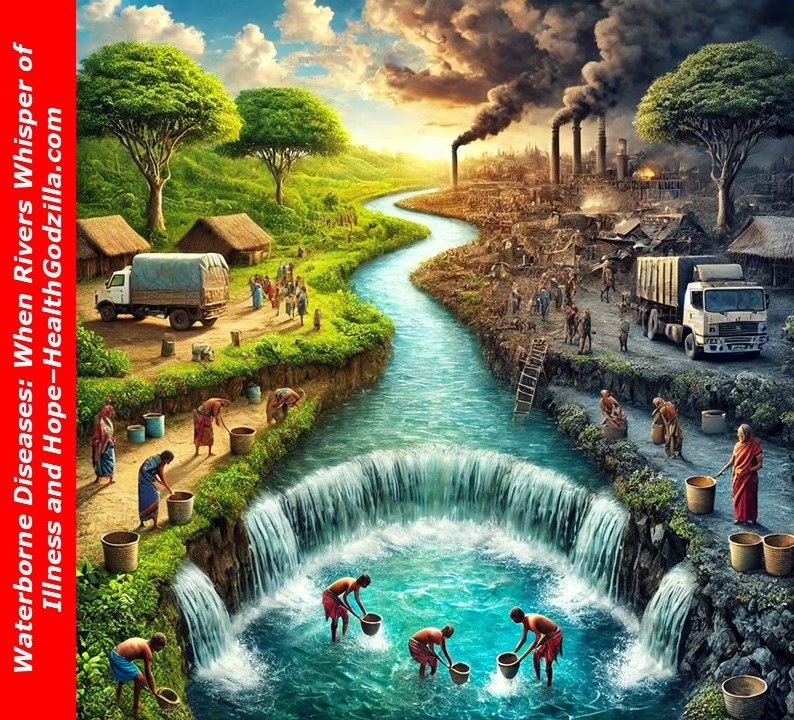

Over the centuries, he had seen it nourish fields into golden abundance, turning soil into bread. At the same time, he had also seen it betray—swollen with unseen parasites, heavy with waste, thick with poisons that stole life instead of giving it. Thus, water was both cradle and coffin, blessing and curse.

“Nothing is more faithful than the river,” Zarvan murmured, “for it always returns to the sea. Yet, nothing is more fickle, for in its clarity hides shadows.”

Here, by the ancient current, he recalled how humanity’s story was always braided with water’s. Progress dammed it, diverted it, drained it. Faith sought it, cities rose beside it, wars were fought over it. Nevertheless, through it all, the river remained what it had always been—an eternal paradox, at once giver and taker.

1. The Silent Spread: A Journey through Time

“Tell me,” Zarvan whispered to the river, “how did you, who carried the first fish and quenched the first thirst, become a bearer of grief?”

The river did not answer in words, but its ripples told the story. Waterborne diseases were not born in laboratories or in the age of factories. Instead, they had always traveled in the current, waiting for the right conditions—when human hands reshaped water’s course and balance broke.

Long ago, cities rose on riverbanks. Stone walls lifted, canals were cut deep, dams reached across valleys. Each triumph of progress bent the river’s will. Nevertheless, nature, as Zarvan knew, never yields without a toll.

In Africa, the promise of irrigation glittered like morning sun on still water. Yet, in those same waters, snails thrived—hosts for parasitic worms. Schistosomiasis crept silently into children’s skin as they played by the banks, leaving their laughter weakened by fevers and fatigue. Rivers once sung of livelihood now murmured of disease.

Further west, in Cameroon, deforestation turned shadows into light. Sun struck open waters, and plants bloomed where forests once stood. The snails rejoiced in this new kingdom. The river, once guarded by trees, now offered itself as a new battlefield—where parasites found eager homes in human bodies. Thus began another chapter in the long history of waterborne diseases.

Zarvan sighed. “Each time we cut, we do not see the other wound we open.” The river had become a mirror of human ambition: reshaped for electricity, for food, for growth—and yet, in that reshaping, invisible enemies were invited to feast.

2. The Children of Water: An Ongoing Crisis

Zarvan walked along the muddy path of a village where children played barefoot, their laughter carried on the breeze. The air was filled with the rhythm of life—yet beneath it lingered an unease, a silence in the bloodstream. For here, the battle was not against soldiers or storms but against the invisible armies hiding in a cup of water.

For the youngest, however, waterborne diseases are merciless thieves. Diarrheal illnesses alone claim over a million small lives each year, striking hardest before a child has even reached five summers. Zarvan had watched mothers cradle limp bodies, whispering lullabies into ears that could no longer hear. Childhood—meant for curiosity and play—was instead spent fighting parasites, bacteria, and time itself.

One afternoon, he saw a woman return from the stream, a clay pot balanced on her head. Her feet were worn, her eyes resigned. She had walked miles for what she believed was life, only to bring home the same water where cattle drank, where insects hovered, where disease nested unseen. To her, clean water was not a right but a faraway miracle.

“Here,” Zarvan thought, “is the cruelest paradox. The source of life becomes the instrument of death.” He remembered how ancient poets once called rivers mothers of abundance. Yet in these places, the rivers mothered sorrow, filling graves faster than granaries—graves carved by the silent march of waterborne diseases.

Meanwhile, children in these forgotten corners did not just wrestle with fever and dehydration. They wrestled with neglect—global systems that looked elsewhere, policies that arrived too late, promises that dissolved before they could be drunk. Each small body lost was not only a child but an unwritten story, an entire future stolen by a single sip.

Finally, Zarvan bent, touched the water with his fingers, and whispered: “You, river, should be their companion in wonder, not their executioner.” The current shimmered but gave no reply.

3. The Global Stage: Water in Crisis

Zarvan crossed oceans and centuries to arrive in Flint, Michigan. At first, water once flowed through pipes with the promise of modernity—treated, measured, guaranteed. Yet when human negligence entered the system, the water turned from guardian to betrayer. Lead seeped through corroded pipes, invisible yet insidious, flowing into the veins of over a hundred thousand residents.

Children drank what should have nourished them and instead swallowed harm. Elevated blood lead levels marked their small bodies with a legacy of stunted growth, faltering cognition, and futures altered before they began. Flint became a wound carved not just in the soil of Michigan, but in the conscience of a nation that had promised safety.

Zarvan listened in silence. “Here,” he thought, “is the mirror of inequality. Even in a land of wealth, it is people with low income, the marginalized, who bear the heaviest thirst.

Moreover, Flint was not alone. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that millions fall ill each year from waterborne diseases and infections—even in industrialized nations. Pipes age, treatment plants falter, and oversight slips. The sickness that haunts villages in sub-Saharan Africa also knocks at the doors of suburban America, only dressed in different names: contamination, corrosion, mismanagement.

Afterward, Zarvan looked west, to deserts where aquifers shrank, and east, to coastal cities where salt invaded drinking supplies. He realized the truth was universal: water insecurity is not bound by geography. Whether in a village well or an urban tap, neglect turns the giver into the taker.

And always, the same whisper echoed through the current: “The river does not discriminate. But human systems do.”

4. A Web of Human Actions and Natural Consequences

Zarvan drifted south, where the Amazon stretched like a living serpent, green and endless. Here once more, human ambition had raised great walls of concrete across rivers, halting currents that once roared untamed. Dams promised light for cities, water for crops, and progress for economies. Yet, in truth, in the stillness behind their walls, new kingdoms stirred.

Stagnant reservoirs shimmered under the tropical sun, breeding mosquitoes in swarms unimagined before. Along with them came malaria and dengue fever, waterborne diseases carried on wings so small yet so devastating. What was meant to electrify villages instead darkened households with fever and loss.

At the Balbina Dam, Zarvan saw how waters had drowned over 2,000 square kilometers of rainforest. Indigenous families were uprooted, animals fled, and the symphony of biodiversity fell silent beneath the flood. In its place, stagnant waters hummed with insect song—a hymn of disease.

“This,” Zarvan reflected, “is the paradox of progress. The power we take from rivers may light a home, but it also lights a path for illness to spread.”

Moreover, the Amazon was not alone. Across Asia and Africa, wetlands drained, rivers diverted, forests felled—all in the name of growth. Consequently, each act of reshaping opened doors to silent invaders: snails that carried schistosomiasis, mosquitoes that thrived where balance had been broken, pathogens slipping easily into human veins. In every case, waterborne diseases became the shadowed cost of progress.

The pattern was clear to Zarvan. Human hands pulled one thread of nature, and the entire tapestry shifted. Rivers remembered every dam, every forest cleared, every wetland drained. In the end, their memory returned not in words but in fevers, in weakened lungs, in graves dug too soon.

“The river does not punish,” Zarvan murmured. “It only reflects what we have done.”

5. Hope in Balance: The Path Forward

Zarvan lingered at the confluence of two streams—one clouded with loss, the other clear with possibility. For though the history of waterborne diseases was long and cruel, it was not without the shimmer of resistance. Humanity, flawed though it is, had begun to listen again to the voice of rivers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, he watched as simple wells were dug, lined with stone, guarded against contamination. He saw schools where children cupped clean water in their hands for the first time, their laughter freed from the shadow of waterborne diseases and fever. Women no longer walked miles to fetch what would betray them, but instead drew life from pumps placed within their villages.

International goals—the Millennium Development Goals first, and later the Sustainable Development Goals—had dared to name water and sanitation as universal rights. Ambitious? Yes. But ambition here was not arrogance, it was necessity. Without safe water, no nation could hope to grow strong, no child to flourish, no future to endure.

Elsewhere, Zarvan walked through wetlands being restored, rivers being given room to breathe again. Engineers and ecologists worked side by side, not to conquer water but to partner with it—allowing wetlands to filter toxins, forests to shield streams, and communities to safeguard their springs. These were not perfect victories, but they were signs of balance rediscovered.

“The road is long,” Zarvan mused. “The wounds of rivers run deep, and the fever of the climate now quickens them. Yet every seed planted in restoration, every drop purified, every child spared is a turning of the tide.”

The challenge ahead was not only to cleanse water but to cleanse the human vision—to remember rivers as companions, not commodities. Only then could the whisper of illness turn again into a song of life.

6. A Final Reflection: Water, the Giver and Taker

At dusk, Zarvan knelt by the river, where twilight painted the current in shades of fire and shadow. He dipped his hands into the water, feeling the ancient pulse. “You have never changed,” he whispered. “It is we who forget.”

Water is the oldest paradox. It nourishes the seed, yet it drowns the field. Ships cross oceans on its back, yet the same current carries waterborne diseases into the mouths of children. A blessing in one moment, in the next it becomes a burial shroud.

For communities across the globe, every drop is a wager: will it heal or will it harm? In Africa, in Asia, in America, the answer is never certain. Flint’s poisoned pipes, the Amazon’s flooded forests, the village stream alive with parasites—each is a reminder that waterborne diseases turn the giver into the taker.

Zarvan listened to the river’s murmur, and he heard not just water but time itself: unyielding, patient, indifferent to empires and policies. “We cannot undo what we have done,” he reflected, “but we can choose differently tomorrow.”

Yet he also knew this truth: leaders may cling to their egos, systems may stall, and promises may dissolve like silt. The river waits for no one. Its memory is longer than our reigns, its justice harsher than our excuses.

Still, Zarvan stood. He believed that in every act of care—every well restored, every wetland reborn, every child spared from fever—there was defiance against despair. Perhaps rivers alone could not bend the will of kings, but they could bend the course of lives.

And as he walked away, the current whispered behind him: “The choice is yours. Do you drink for life—or for death?”

🍂 Hello, Artista

Artista laughed, a warm sound in the damp night. “If rivers could sue us, they’d win every case.”

“Dogs too,” Organum added. “Barku once refused to drink from a bowl that had dust in it. He looked at me as if to say: ‘Do better, human.’”

The Charles River glittered under Boston sun in his memory, while Artista heard the endless rains of Vancouver—sometimes lullabies, sometimes warnings.

“Water is not a resource,” Artista said softly. “It’s a relationship.”

Organum nodded, but then leaned forward, voice low and steady. “And that’s the heart of it. We forget we are not separate. The health of the river, the health of the soil, the health of our bodies—it is all one. One Health. If the river sickens, we sicken. If the soil erodes, so do we. It is not a game of hurting and revenge. It is the simplest law of belonging.”

Artista stroked Whitee’s fur, watching the rabbit twitch with contentment. “Yes. To honor water is to honor ourselves. Neglect it, and the cost comes back—not as punishment, but as consequence. One thread pulled, and the whole fabric quivers.”

They were quiet again, but it was not the quiet of despair. It was the quiet of recognition, of remembering that rivers do not need to forgive or condemn. They only reflect what we give them.

Outside, unseen but ever-present, the rivers went on whispering—not of revenge, but of kinship.

✍️ Author’s Reflection

I was not alone when I wrote this. Others spoke, and I listened. The voices came from rivers choked with silt, from mothers carrying clay pots, from children whose laughter was cut short. They came from Flint’s poisoned pipes and from the drowned forests of the Amazon. And they came from science too—measured in charts and journals, reminding us that what we call “progress” is often borrowed against our own health.

Water, I realized, is not only substance but story. Water holds the memory of civilizations, the scars of mistakes, the resilience of life. Revenge is not its game, nor forgiveness its gift. Instead, it simply reflects.

We are one health—human, animal, river, soil. To wound one is to wound all. If leaders forget this truth, the river will remind us—not with malice, but with consequence.

I do not write with certainty, nor with answers. Only with the hope that in these words, the whisper of rivers may be heard again—not as background noise, but as a call. Perhaps one day we will remember that to honor water is not charity, but survival.

And if a star of wisdom, Noorael, blinked faintly while these words were shaped, let it be known: its light only asks us to remember what we already know.

—Jamee

🌼 Articles You May Like

From metal minds to stardust thoughts—more journeys await:

- AOL-Time Warner failure: Merger, mindsets, and market myths. Explore culture clash, transient advantage, primacy, and antitrust risks.

- Biodiversity and nutrition: Reforming diets through agrobiodiversity. Policy, Traditional and Indigenous Foods, and Scientific Relevance.

Curated with stardust by Organum & Artista under a sky full of questions.

📚 Principal Sources

- World Health Organization, & Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. (2015). Connecting global priorities: Biodiversity and human health: A state of knowledge review. World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Drinking-water. WHO Fact Sheets.

- Ashbolt, N. J. (2004). Microbial contamination of drinking water and disease outcomes in developing regions. Toxicology, 198(1-3), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2004.01.030

- Prüss-Ustün, A., Bartram, J., Clasen, T., Colford, J. M., Cumming, O., Curtis, V., Bonjour, S., Dangour, A. D., De France, J., Fewtrell, L., Freeman, M. C., Gordon, B., Hunter, P. R., Johnston, R. B., Mathers, C., Mäusezahl, D., Medlicott, K., Neira, M., Stocks, M., Wolf, J., & Cairncross, S. (2014). Burden of disease from inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene in low- and middle-income settings: A retrospective analysis of data from 145 countries. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 19(8), 894–905.

- Hunter, P. R., MacDonald, A. M., & Carter, R. C. (2010). Water supply and health. PLoS Medicine, 7(11), e1000361.

- Guerrant, R. L., DeBoer, M. D., Moore, S. R., Scharf, R. J., & Lima, A. A. (2013). The impoverished gut—A triple burden of diarrhoea, stunting and chronic disease. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 10(4), 220–229.

- Hanna-Attisha, M., LaChance, J., Sadler, R. C., & Champney Schnepp, A. (2016). Elevated blood lead levels in children associated with the Flint drinking water crisis: A spatial analysis of risk and public health response. American Journal of Public Health, 106(2), 283–290.

- Fearnside, P. M. (1999). Social impacts of Brazil’s Tucuruí Dam. Environmental Management, 24(4), 483–495.

Relevant chapters and sections were interpreted through a narrative lens rather than cited academically.

Leave a Reply