Prologue — The River Remembers

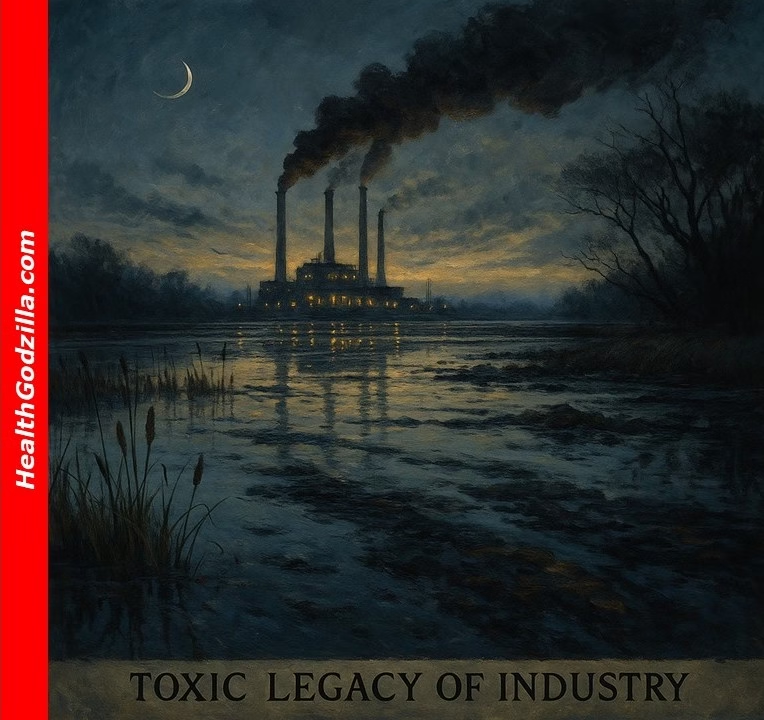

Toxic Legacy of Industry begins where the tide hesitates—

neither rushing in nor drawing back—

and the air tastes of salt, rust, and something the mouth cannot name.

The fishermen call it “a shadow in the water,”

while the scientists call it “bioaccumulation.”

Yet to the river itself, it is simply memory—

a ledger of what the land has poured into it for centuries.

Here, reeds sway in a wind laced with particles invisible yet heavy enough to tilt the scales of life.

Meanwhile, a heron watches from the shallows, its legs thin as calligraphy lines,

patient in the way only creatures shaped by hunger can be patient.

Below, mussels filter what they believe is food,

layering their shells with the quiet sediment of human ambition.

Farther upstream, a smokestack exhales into the sky—

not with urgency, but with the casual persistence of a clock ticking in a locked room.

And it does not roar; instead, it whispers,

for it knows that the real change is never immediate.

The river knows this too,

and therefore it waits.

Mirror I — Where the Shoreline Learned New Names

Once, the tide’s rhythm followed the moon alone.

Now, however, it also answers to the factories whose outflows braid themselves into the estuary’s veins—

a toxic legacy of industry written in currents and silt.

Here, heavy metals, PCBs, and persistent organic pollutants—

names like industrial ghosts—arrive uninvited,

traveling through barrels of rainwater and snowmelt,

and leaking from soil that still remembers every spill.

So, here is the first mirror:

water, deceptively clear,

reflecting clouds while holding within it an archive of all that industry has ever chosen to forget.

Meanwhile, the fish still leap in early morning light,

and their silver arcs fool the untrained eye into thinking the world is well.

Yet their flesh tells another story—

one you cannot see without a scalpel and a microscope,

or without the grief of a community that has tasted it for far too long.

Moreover, the invasion is not of a creature crossing an ocean in a ballast tank—

rather, it is the arrival of chemistry into bodies it was never meant to meet.

Thus, cadmium finds the gills,

while mercury settles in the liver,

and PCBs nest in fat.

As a result, predators carry the highest burden—

ospreys, seals, and even the people who pull nets from these waters.

The scientists call it biomagnification.

The old fishermen, on the other hand, just say, “It climbs the chain, like debt.”

Mirror II — Where the Marsh Learns to Keep Secrets

The wetland is not an innocent witness.

It receives, filters, buries—

layer upon layer of silt and leaf-litter folding over what the river carries.

To the passing eye, it is all grace—

egrets rising like pale prayers, sedges combing the wind.

But beneath the green skin, the sediment keeps accounts in heavy script:

arsenic, lead, dioxins, hydrocarbons—each a page in the toxic legacy of industry.

Roots reach down into this ledger,

drawing up water clouded not with clay, but with the chemistry of a century’s commerce.

The cattails grow tall,

the frogs still sing in spring,

but their blood tells of a burden they never chose.

Here the legacy changes tempo.

It slows.

It waits.

Pollutants bind to soil particles, resting in the anaerobic dark—

not gone, only patient.

A storm, a dredging, a careless anchor—any of these can stir the archive back into circulation.

Generations pass.

Children grow where their grandparents once gathered clams.

Some of those clams still live,

though their shells are thinner, their bodies richer in metals than in meat.

The wetlands endure,

but they do not forgive.

Mirror III — The Long Memory of Water and Silt

What the marsh hides, the marsh remembers.

Every flood writes a new line; every drought seals the ink.

The chemical ghosts—mercury from forgotten tanneries,

chromium from shipyard paints,

PCBs from transformers now long dismantled—

settle in like unwanted tenants who never leave,

each carrying a verse in the toxic legacy of industry.

They move slowly, almost with dignity,

creeping molecule by molecule into food chains.

A minnow swallows a silted insect larva;

a heron swallows the minnow;

a child watches the heron and breathes the damp air—

and so the ledger writes itself into bone, feather, and lung.

Industry may close its gates.

The last smokestack may be felled.

But the marsh does not care for calendars.

Its clock runs on half-lives and binding affinities,

measured in decades and centuries.

And somewhere far downstream,

in a bay that thinks itself untouched,

a crab carries the signature of an inland factory fire from fifty years ago.

The water knows the way.

The silt remembers the tune.

And when the wind sweeps low over the reeds,

you can almost hear it hum—a song of patient ruin,

and of the strange beauty that still blooms despite it.

Closing Arc — The Wetland’s Last Lantern

Night comes first to the water.

Long before the forest turns shadow,

the marsh pools are already black glass,

reflecting only the patient stars.

This is when the voices return—

not loud, but braided into the breathing of reeds,

into the slow push and pull of the tide.

No scolding. No pardon.

Only the truth of what they saw.

They speak of barges heavy with ore,

of pipe mouths dripping solvents like slow venom,

of winters when the fish died and summers when they sang.

They speak of herons that learned to hunt in poisoned shallows

and of children who waded through cattails,

their laughter rising with dragonflies,

unaware they were playing inside the toxic legacy of industry.

The wetland does not ask us to worship it.

It asks us to remember.

Because forgetting is the first pollution,

and memory—when tended—can be a lantern bright enough

to guide us through the fog.

So we leave it here—

in the belly of the beast,

in the marrow of the tide,

in the still eye of the marsh—

a place that carries both our trespass and our possibility.

And if we lean close enough to the water’s skin,

we may hear the softest truth of all:

the world is not waiting to be saved—

it is waiting to be met,

honestly,

before the last lantern goes out.

🍂 Hello, Artista

Artista leaned against the rail of the small footbridge, her breath curling in the cool night air. Below, the wetland shimmered faintly, as if the moon had stitched silver into its skin.

“Do you hear it?” she asked.

Organum tilted his head. “The frogs?”

“No,” she smiled, “the quiet.”

He followed her gaze to the black mirror of water. “It’s not really quiet. It’s the kind of silence that’s busy with listening.”

A reed swayed, and somewhere a splash marked a fish’s brief rebellion against the dark.

“They carry all of it,” Artista said, “our damage, our care, our forgetting, our return.”

Organum’s voice softened. “And maybe they carry our promises too—ones we haven’t yet found the courage to make.”

They stood like that for a while, the bridge holding them above the stillness, the wetland holding the world’s oldest patience beneath them.

When they finally turned to go, Artista glanced back and whispered to the water, “We’ll try to meet you before the lantern goes out.”

And though no one could prove it, the marsh seemed to nod.

✍️ Author’s Reflection

I did not come here to write of wetlands as if they were a chapter finished long ago.

I came because they are still speaking—

and because I have learned that listening is an act of repair.

This piece did not grow in isolation.

It took shape with the voices of scientists tracing chemical shadows,

with the memories of those who saw waters dim and then stir again,

with the quiet counsel of stories older than any measurement.

The wetland’s story is not mine,

but I have walked far enough beside it to feel the rhythm of its pulse.

If the toxic legacy of industry has left scars,

it has also left a question:

how much of ourselves do we leave behind in the water?

That question will follow me,

as will the knowledge that recovery is not a return—

it is a new shape, carrying the weight of what came before.

I was not alone when I wrote this.

Others spoke, and I listened.

—Jamee

🌼 Articles You May Like

From metal minds to stardust thoughts—more journeys await:

- AOL-Time Warner failure: Merger, mindsets, and market myths. Explore culture clash, transient advantage, primacy, and antitrust risks.

- Biodiversity and nutrition: Reforming diets through agrobiodiversity. Policy, Traditional and Indigenous Foods, and Scientific Relevance.

Curated with stardust by Organum & Artista under a sky full of questions.

📚 Principal Sources

- World Health Organization, & Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. (2015). Connecting global priorities: biodiversity and human health: A state of knowledge review (Chapter: Agricultural biodiversity, food security and human health).

- Havel, J. E., Kovalenko, K. E., Thomaz, S. M., Amalfitano, S., & Kats, L. B. (2015). Aquatic invasive species: Challenges for the future. Hydrobiologia, 750(1), 147–170. Available at PubMed

Relevant chapters and sections were interpreted through a narrative lens rather than cited academically.

Leave a Reply