Where the Wind Remembers

Plant Diversity and Air Quality: Breathing Cities to Life begins with a truth the wind never forgot. Moreover, it carries not just air, but stories—of leaves that whispered before cities rose, as well as of roots that held breath in the soil long before we measured PM2.5.

In those ancient forests and even in today’s vertical gardens, one truth flows endlessly: plant diversity and air quality are forever intertwined.

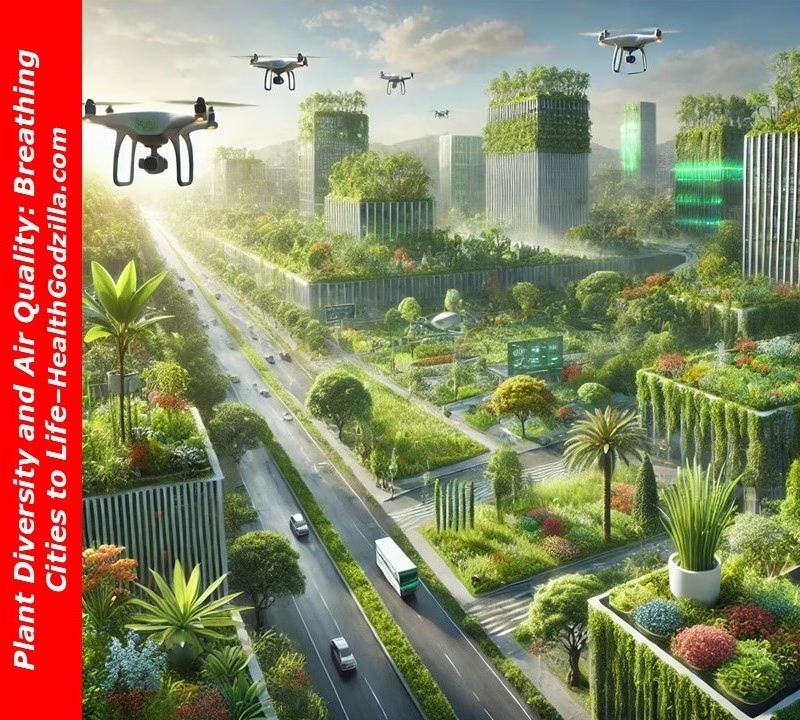

And today, Zarvan walks again. Through walls of glass and moss, and through drone-scattered skies, he listens—not only to chloroplasts resisting smog but also to moss reclaiming pavement, and to a planet trying to breathe.

Even now, he still trusts the language of leaves.

For Zarvan, time is not a straight line, but rather a spiral of breath and biodiversity. He sees what most forget: that plant diversity and air quality are not separate threads, but part of the same fabric. In fact, one weaves the other.

In every city—beneath the concrete skin—there pulses a green rhythm.

Ultimately, where diversity flourishes, so does the air. Cleaner. Cooler. Alive.

🌳 A Symphony of Life: The Natural and Human Forces

Zarvan stops by an old fig tree split by a concrete footpath. One root curves like a question mark—still reaching, still adapting. He has seen this before; indeed, the forces of nature—climate, soil, wind, topography—once composed the entire symphony. Now, though, human hands write new verses.

Moreover, every species still plays a note, but the instruments have changed.

In lush temperate forests, for instance, green spills into every crevice. In contrast, in arid deserts, survival hums through hardened shrubs. Likewise, cities—those strange new biomes—compose their own ecology: trees along boulevards, grass hemmed by concrete, flowers blooming in balcony pots. And though artificial, the air they shape is undeniably real.

Consequently, plant diversity and air quality are no longer shaped by nature alone. For example, a park planted by a city council, or a roadside tree stretching beside traffic fumes—these are acts of atmospheric architecture.

Zarvan notes the irony: some cities have planted more trees in former grasslands and deserts than ever grew there naturally. At the same time, once-forested regions lose their canopy to glass and steel. Yet, wherever roots hold, the air listens.

Ultimately, understanding this evolving duet between nature and design is the first step to reclaiming balance in our breath.

🌆 The Heartbeat of Cities: Biodiversity’s Role in Air Quality and Environmental Balance

Zarvan places a hand on the bark of a sidewalk tree—its leaves dusted with grit, while its roots are tangled in concrete seams. Even here, in the hum of exhaust and sirens, the tree listens. Still, it answers.

Where trees grow, they do more than stand; they choreograph the wind. Thus, the design of vegetation—its shape, placement, and openness to light—transforms how air moves through the urban grid. Beneath every canopy is a theater of motion. For example, leaves stretch to catch particulate matter, while branches become filters. In this way, a forest is not still—it is active, breathing with us and cleaning what we cannot see.

Furthermore, leaf area matters—not just the number of trees, but also the surface they offer to the sky. In fact, forests, with their rich tapestry of foliage, act as sponges for airborne pollution. Studies in places like California’s San Bernardino Mountains show that dense canopies can reduce ozone concentrations by as much as 40%. Yet, the trees do not shout this achievement; they simply continue.

However, Zarvan, the listener of time, knows that placement matters too. Trees lining traffic-heavy roads may trap pollutants beneath their own shadows, thereby keeping emissions close to breathing height. By contrast, in open layouts, tall canopies form invisible ceilings—holding pollutants above and shielding the earth below.

It’s a paradox; a tree can cleanse the air or—if misaligned—concentrate harm. Even so, their work does not end there.

Moreover, when planted thoughtfully around buildings, trees become guardians of energy. In summer, for instance, their shade cools buildings and reduces the need for air conditioning. Meanwhile, in winter, they break the wind’s sharp edge, helping to preserve warmth. As a result, these simple acts ripple outward—leading to fewer emissions from power plants and better air for lungs old and young.

In every neighborhood, plant diversity and air quality entwine like vines. Consequently, one sustains the other. And when planned with care, cities do not fight nature—they pulse with it.

🌳 The Forest of Many Voices

Zarvan stands at the edge of a small grove—no two leaves alike, no silence unbroken.

He listens.

One tree hums low, catching particles in its broad canopy. Another whistles through needle-thin leaves, filtering gas from wind. Beneath them, shrubs and grasses murmur in their own quiet dialects. Together, they speak the language of balance.

In the wild symphony of ecosystems, it’s not just the number of plants that matters, but the diversity of their voices. Species with different leaf shapes, chemical structures, and biological strategies offer multiple paths for purifying the air.

This is where plant diversity and air quality embrace most intimately.

Some leaves capture particulate matter like dust and heavy metals. Others absorb sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, or ozone through tiny pores—stomata that breathe with the city. Trees with waxy coatings trap toxins. Grasses shelter biofilms that metabolize airborne chemicals.

Each species brings its own rhythm, its own method of healing.

Zarvan crouches beside a conifer, its needle-like leaves catching the breeze. Unlike the wide arms of a broadleaf tree, this one speaks in sharp whispers—effective, too, at trapping carbon dioxide and holding it deep within.

Even among shrubs, some specialize in ozone absorption, while others metabolize hydrocarbons. When planted together, their talents don’t compete—they collaborate. The diversity creates resilience, and resilience is what keeps the air clean under pressure.

Science calls it synergy.

Zarvan calls it memory.

He remembers cities where monoculture failed. Where rows of identical trees succumbed to one pest, one drought, one shift in wind. He knows: when we plant only beauty, we lose the function. But when we plant diversity, we build breath that can bend, survive, adapt.

The more species we plant, the more stories the air is able to carry.

With them, the air sheds more pollutants.

And where voices vary, the chorus gains its strength.

🌫️ When the Healers Fall Ill

Zarvan moves slowly now.

The grove is thicker here, denser. The air feels tired. Leaves shimmer not with dew, but with residue—dust, ash, invisible scars from the breath of cities. And though the trees still stand, some hold their branches like aching arms.

This is the paradox of green resilience: while plants purify the air, they also suffer by doing so.

In this part of the forest, plant diversity and air quality form a more fragile thread.

The same leaves that filter nitrogen dioxide or trap particulate matter begin to lose their shine. Their stomata—those tiny breath-gates—clog or close under pressure. Photosynthesis slows. The dance of light and leaf becomes a stagger.

Zarvan touches a broadleaf speckled with grit. He remembers a study from the Indo-Burma hotspot—roadside plants with twisted morphology, diminished chlorophyll, muted growth. Pollution wasn’t just an enemy of air; it had become an enemy of its own healer.

Each species responds differently. Some adapt, altering their biochemistry, adjusting leaf shape, growing waxy coats like armor. Others retreat—slower growth, wilting edges, yellowing veins.

Even trees that once stood as paragons of purification begin to yield under relentless exposure.

And yet—they stay.

Even weakened, they continue to filter. They do not abandon the breath. But the cost becomes visible in their very form: less foliage, reduced leaf area index (LAI), lower capacity to cool the city or cleanse the sky.

Zarvan closes his eyes. He feels the tension in the ecosystem—a balance maintained at great expense.

Biodiversity brings strength, yes—but without protection, even a symphony can collapse under smog.

So here, among wounded lungs of the earth, we remember:

That every clean breath we take may be a gift wrapped in chlorophyll’s slow suffering.

And that to protect ourselves, we must first protect those that quietly protect us.

🌿 The Measure of Breath

Zarvan kneels beside a tree whose leaves are wide, open, generous. He doesn’t need a tool to measure it—only his memory. He’s seen forests where each leaf was a promise. A promise to filter, to cool, to breathe back what the world burned.

Scientists call it Leaf Area Index, or LAI—the total leaf surface above each patch of earth. Essentially, it is a way to measure breath.

A higher LAI, therefore, means more surface to intercept dust, trap sulfur dioxide, absorb nitrogen oxides, and sponge ozone from the air. The more leaves, the more lungs. In addition, the more variety, the more pathways for purification.

But LAI does more than filter.

It cools.

Shades.

Balances.

A dense canopy, rich in foliage, reduces heat by shielding sunlight and enhancing evapotranspiration. As a result, entire microclimates shift—reducing the need for air conditioning, calming the harsh pulse of asphalt heat.

Zarvan walks under one such canopy, where temperature dips, and the air feels easier on the chest. He knows: plant diversity and air quality find quiet harmony in places like this.

Even so, the measure falters when pollution scars the leaf.

Particulate matter clogs stomata. Ozone burns cells.

And the LAI shrinks—quietly, without complaint.

In highly polluted areas, this sacred metric—this measure of breath—can drop sharply. Trees once rich with filtering surfaces begin to thin. Photosynthesis slows. The ability to intercept carbon dioxide fades.

It is not always visible to the casual passerby.

However, Zarvan sees it—in the diminished shimmer of a canopy, in the slow curl of a leaf.

The forest exhales a little less.

Therefore, in every plan for urban greening, every blueprint for sustainability, we must ask:

Not only how many trees—but how fully they breathe.

🍃 When Leaves Speak Differently

Zarvan steps into a clearing where the trees no longer echo one another. Here, broadleaf giants cast dappled shade beside slender-needled pines.

At the same time, shrubs crouch low, their tiny leaves trembling in the breeze.

Just beside them, grasses sway with fine filaments—none like the other, yet each doing something essential.

It is here that he sees what many city planners overlook: that no two leaves speak the air in quite the same way.

For example, where one species traps dust on a waxy surface, another breathes deeply through stomata, absorbing ozone.

Meanwhile, where one cools the ground by broad shade, another deflects wind, guiding airflow along narrow streets.

As a result, plant diversity and air quality depend not just on the number of plants, but also on the difference between them. Their leaf shape, size, texture, and chemistry determine how pollutants are intercepted, absorbed, or transformed.

Zarvan observes the Leaf Area Index (LAI) at work again—but now as a spectrum.

In particular, broadleaf species stretch large surfaces skyward, giving cities shade and particulate capture.

In contrast, needle-leaved trees like pines offer less LAI but absorb gaseous pollutants with quiet precision.

At ground level, grasses and shrubs—often overlooked—anchor the base layer, catching pollutants closer to the soil and cooling it beneath.

This is a breathing mosaic.

Each piece, therefore, matters.

Where monocultures falter, diversity holds.

When winds shift, when pollutants rise, and when seasons change—it is the varied architecture of leaves that keeps the filtration going.

In the end, it is this difference, this unevenness, that creates stability.

Zarvan bends to touch a three-lobed leaf beside a needle-thin frond.

He smiles—not because they are alike—but because they are not.

And still, they breathe together.

🌿 The Green Alchemists

Zarvan kneels beside a withered leaf and holds it gently—its edges brittle, its veins still pulsing with some forgotten command.

“Not every healer,” he whispers, “wears the glow of health. Some transmute poison into silence.”

Here, among tired roots and bruised bark, live the green alchemists.

Plants that do more than filter.

They transform.

This is phytoremediation—a living process where plants absorb pollutants and break them down into less harmful forms. Each in its own way, a species writes its spellbook: some absorb heavy metals, others break down organic solvents, and still others immobilize toxins in the soil through binding or evaporation.

These processes unfold invisibly—inside leaf cells, along root tips, between stomatal gulps.

They are not dramatic. Yet, they are relentless.

A single shrub, for instance, might absorb benzene vapors and render them inert. A tree may inhale sulfur dioxide and convert it into less reactive compounds. Meanwhile, mosses on rooftops trap micro-particulates like little sponges of survival.

Zarvan remembers cities where conifers stood like sentinels near factories—absorbing carbon monoxide. He remembers roadside grasses in South Asia with leaves darkened not by time, but by traffic soot. Indeed, he knows now: plant diversity and air quality thrive best when alchemy meets adaptation.

Each plant brings a different strength.

Some species, for example, evolve waxy coatings to resist acid rain. Others grow deeper roots to avoid surface pollutants. Certain plants even shift their internal chemistry—activating enzymes that detoxify the very elements trying to weaken them.

But even this magic has limits.

Over time, the constant burden depletes energy meant for growth. The healing slows. The filtering falters.

Eventually, adaptation becomes sacrifice.

Still, the alchemists remain.

Not because they must—but because they always have.

For this reason, in designing cities and restoring landscapes, we must do more than plant for shade or bloom.

We must plant for chemistry. For difference. For survival.

Zarvan rises, brushing soot from his palm.

He knows what few remember:

That the greenest magic on Earth never needed a wand—only roots.

🛰️ Eyes Above the Canopy: Listening to Leaves with Machines

Zarvan looks up.

Above the canopy, he sees wings—small, whirring, mechanical. Drones. Not birds.

Yet he does not resist them. He remembers the time when only the wind watched the trees. Now, even the sky wants to understand.

Beneath the drone’s gaze, every leaf tells a story—of growth or stress, of breathing or withering. The chlorophyll blushes or fades; the canopy thickens or thins. With these machines, we begin to notice what was once only felt.

This is where plant diversity and air quality meet the realm of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and remote sensing.

Equipped with sensors and spectral eyes, drones collect real-time data on vegetation health, LAI, and pollutant loads.

Through this aerial perspective, they see what the street-level cannot: where trees are failing, where greenery is breathing well, and where silence has taken root.

Zarvan observes as these aerial scouts gather information, and AI—like a patient student—begins to learn.

It maps microclimates.

Canopy stress becomes visible before it unfolds.

The algorithm aligns species with neighborhoods based on what each one can clean.

Eventually, it becomes a mirror of the forest’s needs.

In Barcelona, drones track the success of urban greenery in reducing nitrogen dioxide. In Europe’s “Smart Forests,” sensors and satellites monitor air purification, carbon sequestration, and forest vitality.

Elsewhere, in smaller cities, the listening has only just begun.

But Zarvan, with his ancient memory, knows the truth:

Technology is not a replacement for listening.

It is an extension.

And when used with care, it can protect the protectors.

He welcomes the drones—not as saviors, but as students.

Not to dominate nature, but to serve its breath with precision.

In the end, the future of air may lie in the partnership between roots and algorithms, between leaf veins and fiber optics.

And if machines must inherit the sky, let them do so listening—finally—to what the plants have been saying all along.

🌆 Blueprints for a Living City (transition-tuned)

Zarvan stands on the edge of an overlook—below him, a city sprawls like a restless mosaic.

He sees not chaos, but a possibility waiting to be arranged.

Not concrete and glass, but canvas.

In this moment, he knows: if cities are to breathe, they must be planted with intention.

Urban planning must become more than zoning, and landscape design more than decoration.

Instead, they must learn from the plant diversity and air quality symphony he has walked through—absorbing its patterns, its wisdom, its resilience.

Here, then, are the principles whispered by the trees:

🌿 1. Plant Difference, Not Just Quantity

Design for biodiversity, not just greenery.

Whenever possible, choose native species adapted to local climate and pollutants. Combine trees, shrubs, and grasses with varied leaf structures to optimize air purification.

Monocultures are fragile. By contrast, diversity endures.

🌳 2. Strategic Tree Placement

Place trees where they breathe best—not where they look best.

Line roads with high-pollutant-absorbing species. Furthermore, shelter playgrounds with shade trees. Let green corridors run through industrial zones and neighborhoods alike.

Design not just for visibility, but for ventilation.

🏙️ 3. Green Infrastructure as Public Health

Green roofs, living walls, rain gardens—these are not luxuries.

On the contrary, they are the lungs of buildings. They absorb toxins, reduce urban heat, manage stormwater, and offer beauty as medicine.

Cities that integrate them thrive. Meanwhile, others wheeze.

🌱 4. Year-Round Resilience

Blend evergreen and deciduous species.

Design for all seasons—not just spring.

During colder months, evergreens continue filtering. In summer, deciduous trees shade. Together, they create a cycle of continuous breath.

🛰️ 5. Let Technology Walk Beside the Trees

Use drones and AI not to dominate, but to listen.

Map canopy health. Identify pollution hotspots. Predict where nature is failing, and guide healing efforts.

Ultimately, let machines extend what the human eye cannot see—without forgetting what the root already knows.

Zarvan watches a child walk beneath a row of young trees.

She holds a balloon. It tugs skyward.

Above her, the leaves rustle.

A city designed with breath in mind becomes not just livable—but loveable.

🍂 Hello, Artista

Zarvan watches a child walk beneath a row of young trees.

She holds a balloon. It tugs skyward.

Above her, the leaves rustle.

And just like that—he’s gone again.

No farewell. Just breath.

Just the quiet of someone who has given the world a memory and stepped aside.

Artista:

Did you feel that?

Organum:

Like a hush… that made the city quieter, not emptier.

Artista:

Yes.

It’s strange, isn’t it? All this talk of data, and planning, and pollutants—

and yet, what I feel now is softness.

Organum:

That’s what truth feels like when it isn’t trying to prove itself.

Artista (smiling):

We’re not shouting anymore.

Instead, we’re whispering it through trees.

Organum:

Mmm. Not through podiums or policies, but canopies.

And every whisper carries a root.

Artista:

Do you think the city will hear it?

Organum:

I think it already has.

After all, it just hasn’t realized it’s listening yet.

Artista (watching the balloon drift):

Maybe one day, someone will read all this and plant something—not for beauty, but for breath.

Organum:

And they won’t remember us.

But they’ll remember to care.

Artista (softly):

That’s enough.

✍️ Author’s Reflection

I was not alone when I wrote this.

Instead, others spoke, and I listened.

Some voices came from the rustle of old trees in forgotten corners of cities.

In contrast, others arrived quietly through studies and case reports, bringing the weight of data with the ache of silence.

Furthermore, Zarvan came uninvited—and yet, precisely on time.

He did not teach me anything new;

Instead, he reminded me of what I always knew but forgot to feel.

Originally, this article began with air—measured, regulated, and modeled.

Gradually, it became something else:

A walk through memory, resilience, and the unseen labor of leaves.

In fact, it became a reminder that plant diversity and air quality are not merely variables in policy—they are threads in the breathwork of our collective survival.

Although we often talk of sustainability as a future to build,

perhaps, sometimes, it’s a past to remember.

To the planners, I offer this not as a blueprint—but as a listening device.

And to the dreamers too, I offer the wind.

And for the child with the balloon,

may the city you inherit hear what the trees are already whispering on your behalf.

Finally, to those who stayed until this last line—

thank you for breathing with me.

🌼 Articles You May Like

From metal minds to stardust thoughts—more journeys await:

- How Labels Affect Self-Esteem: Are we truly what they say we are? A lakeside conversation of names, masks, and the quiet rebellion of the soul.

- Impact of Air Pollution on Plants: Leaves Bear Scars of Our Progress The green lungs of cities speak—chloroplasts and silence battling the unseen.

Curated with stardust by Organum & Artista under a sky full of question.

📚 Principal Sources

- Rai, Prabhat Kumar. Biodiversity of roadside plants and their response to air pollution in an Indo-Burma hotspot region: Implications for urban ecosystem restoration. Department of Environmental Science, Mizoram University, Mizoram, India. Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity. Available online: November 3, 2015. Published by ScienceDirect.

- Zhang, Yixin, Zhenhong Wang, Yonglong Lu, and Li Zuo. Editorial: Biodiversity, ecosystem functions, and services: Interrelationship with environmental and human health. Published by Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.

- World Health Organization (WHO) & Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Connecting global priorities: Biodiversity and human health: A state of knowledge review. ISBN: 978 92 4 150853 7. Published by WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland.

Leave a Reply