Prologue — Where the Fields Begin to Forget

Climate and Traditional Food Transition does not begin in policy rooms or market reports. Instead, it begins quietly in the field itself, long before anyone names it.

The land does not forget all at once.

Rather, it forgets slowly, the way a hand loosens its grip without realizing it.

Once, the fields spoke in many tongues.

Grains of different heights bent differently to the same wind; meanwhile, leaves carried shades of green that no single name could hold. Seeds remembered seasons—dry years, wet years, and years when the river arrived early or not at all. In those days, diversity was not an argument; instead, it was habit. It lived in soil, in seed jars, and in the rhythm of cooking fires.

Now, however, the silence arrives without announcement.

Climate does not knock.

Instead, it enters.

It arrives as warmer nights when crops no longer rest.

Sometimes it shows itself through rains that forget their old calendars.

Elsewhere, pests begin traveling farther than memory once allowed.

As a result, soils tire more quickly than before.

At first, nothing feels dramatic. Nothing appears headline-worthy.

Yet gradually, fewer varieties are planted. Fewer seeds are saved. Consequently, choice narrows, although it does not feel like a choice at all.

This is how food begins to change—not through decision alone, but through consequence. Climate and Traditional Food Transition unfolds here, at the meeting point of pressure and adaptation.

Markets adjust to the climate. Subsequently, diets adjust to the markets. Over time, plates begin to mirror a smaller landscape. What grows easily survives; meanwhile, what struggles fades. Traditional foods, once shaped by patience and place, start slipping out of daily life—not because they are rejected, but because the conditions that held them steady begin to loosen.

Thus, the nutrition transition does not announce itself as a rupture.

Instead, it arrives disguised as convenience, adjustment, even survival—more response than preference.

And so, the fields begin to forget.

Not the people yet.

Not entirely.

Still, the land carries the first signs—quiet, persistent, written in what no longer grows where it once did. Therefore, before facts appear and before numbers arrive, the ground already knows what is shifting.

This is where the story begins.

1. The Climate That Rearranges Our Plates

Climate changes the menu long before it changes the mind.

At first, the shift appears subtle. Growing seasons stretch or shrink by a few weeks; meanwhile, rainfall hesitates, then arrives all at once. Heat lingers into nights that once cooled the soil. Consequently, crops respond—not with words, but with yield, timing, and quiet refusal.

In this way, Climate and Traditional Food Transition moves from the sky into the field.

Traditionally, food systems grew in dialogue with place. Farmers chose varieties because they endured heat, welcomed floodwater, or ripened before drought tightened its grip. Over generations, taste followed ecology. Dishes formed around what survived, not around what traveled well. Therefore, cuisine became a map—of climate, of patience, of local knowledge.

However, climate pressure disrupts this conversation.

As temperatures rise, familiar crops lose reliability. As rainfall grows erratic, sowing calendars blur. Moreover, pests and plant diseases expand their ranges, arriving where memory holds no defense. Because of this, farmers begin to favor varieties that promise uniformity and speed, even if they carry less diversity in the field and on the plate.

Gradually, adaptation narrows choice.

What endures climate stress most efficiently often becomes what markets reward. Consequently, diets reorganize around fewer crops—those that tolerate transport, storage, and scale. Meanwhile, traditional foods that once thrived under stable patterns slip into the margins, not because they lack value, but because the climate they evolved with no longer holds steady.

Thus, climate does not only reshape agriculture; it reshapes eating.

The nutrition transition gains momentum here. As environmental pressure increases, food systems lean toward calories that are predictable rather than nutrients that are diverse. Over time, plates begin reflecting resilience strategies rather than cultural preference. In other words, survival quietly edits tradition.

Still, this is not a story of collapse.

Instead, it is a story of rearrangement.

Climate rearranges what grows. That, in turn, rearranges what is cooked. Eventually, what is cooked rearranges what is remembered. Traditional food systems begin adjusting—sometimes resisting, sometimes yielding—while biodiversity absorbs the strain first, and most silently.

Before policy responds and before data confirms the trend, the table already knows:

the climate has changed, and with it, the order of food.

The climb continues.

2. When Traditional Food Systems Hold Their Ground

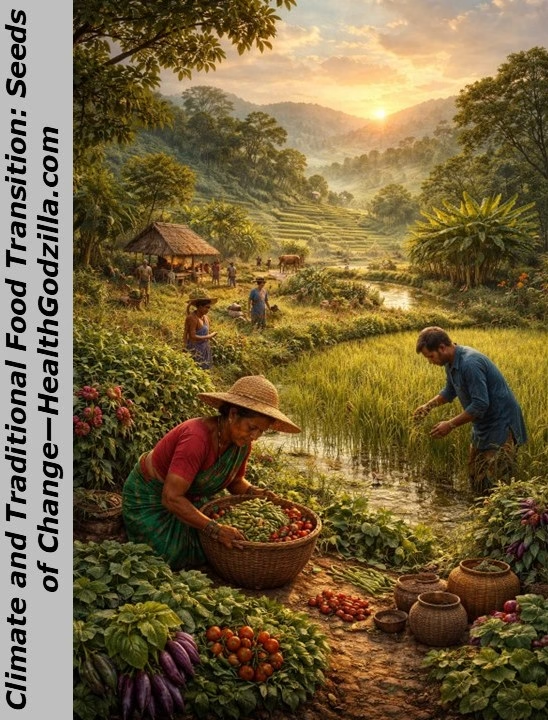

In the early light, an elder runs fingers through a cloth pouch of seeds.

Some are small and dark, others pale and uneven. None look identical.

They are returned to the shelf without counting—only a nod, as if the hand already knows which season is coming.

Outside, the air feels unfamiliar, but the seeds remain patient.

In many places, tradition does not stand like a museum piece. Instead, it stands like a tree line in wind—bending, adjusting, yet still holding the soil.

Ancestral cuisines were never only about taste. Rather, they were about timing. They were about what ripens before the heat hardens the ground, and what survives after the rains have spent themselves. They were about balance, too—grains with legumes, roots with greens, sour with bitter, stored with fresh. Consequently, a “dish” became more than a meal; it became a small local treaty between body and landscape.

Even now, that treaty survives in fragments.

A clay jar of seeds kept away from damp corners. A grandmother’s habit of drying leaves when the sun is steady. A farmer who still plants more than one crop because the sky has become unpredictable. Meanwhile, a child learns the name of a grain not from a textbook, but from the sound it makes in a pot.

This is seed memory—not romantic, not mystical, simply practical. Variety is insurance. Diversity is the quiet math of survival. Therefore, traditional food systems do not rely on one crop, one season, one promise. They spread risk, and in doing so, they spread nourishment.

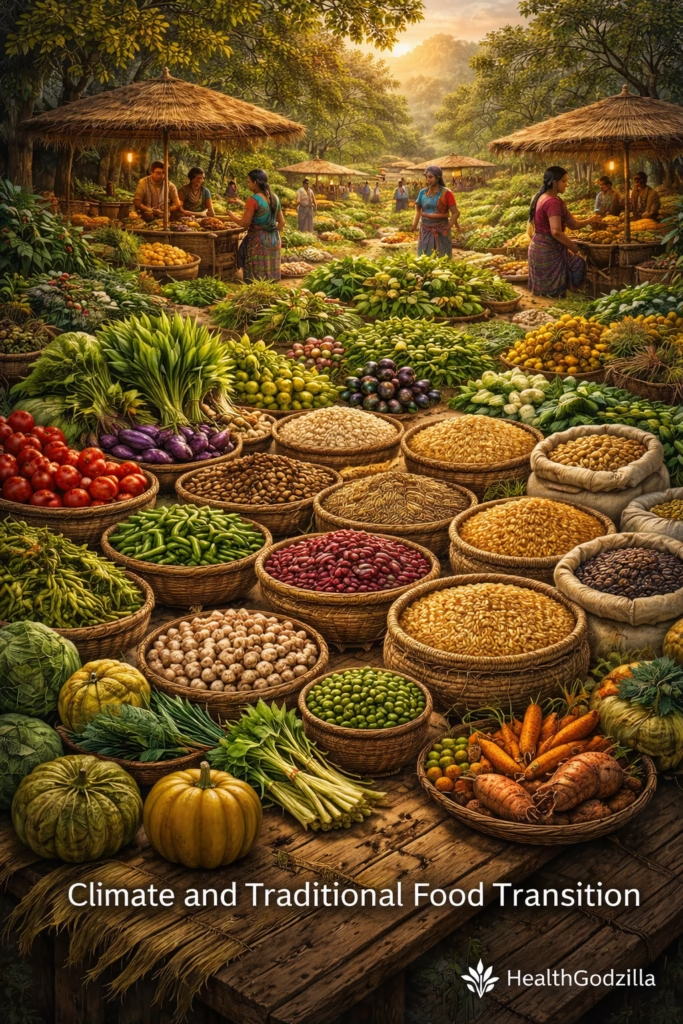

Moreover, these systems carry biodiversity in ordinary forms. A single community may draw food from many species across fields, home gardens, water edges, and fallow patches. Likewise, within one crop, many varieties can exist—each with its own tolerance, yield, taste, and timing. This is why older diets often held more micronutrient richness without speaking the language of “micronutrients.” They did not measure health in charts; instead, they measured it in strength, recovery, endurance, and the absence of certain illnesses that now feel common.

Still, the deeper strength of tradition lies in its ecological logic.

Traditional dishes often match local ecosystems because they were shaped by them. Fermentation, for example, extends shelf life when harvests arrive in bursts. Drying and pickling preserve nutrients when seasons turn harsh. Mixed meals—grains with pulses, greens with oils—build completeness when single foods cannot. Consequently, what looks like culture is also strategy. What looks like habit is also adaptation.

So, even as Climate and Traditional Food Transition accelerates, traditional systems do not vanish everywhere at once. Instead, they hold their ground where memory remains active—where seeds are saved, where seasonal foods still matter, where local crops still have a place on the table.

This is not nostalgia. It is resilience wearing familiar clothes.

And yet, resilience is not stubbornness. It is intelligence that stays flexible. In the next bend of this story, we will see how that intelligence gets strained—not only by climate, but also by the speed of markets and the hunger for uniformity.

The ground holds, for now.

But the pressure keeps arriving.

3. Nutrition Transition — When Diversity Thins Out

The change does not arrive as hunger.

It arrives as replacement.

At first, the table still looks full. Calories remain available; sometimes they even increase. However, variety begins to retreat quietly. Fewer grains appear. Fewer greens return with the seasons. Slowly, the plate starts repeating itself.

This is how the nutrition transition takes shape—not through absence, but through narrowing.

As climate pressure unsettles fields, food systems seek stability. Consequently, crops that mature quickly, store easily, and travel far begin to dominate. Markets adjust first. Then kitchens follow. Over time, diets reorganize around what is reliable rather than what is diverse.

Thus, abundance survives, but complexity thins.

Traditional food systems once drew nourishment from many directions at once—fields, gardens, water edges, fallow land. Meals carried layered logic: bitter to balance sweet, fermented to steady digestion, pulses to complete grains. Yet as food systems accelerate, these slow arrangements struggle to keep pace. Convenience replaces sequence. Uniformity replaces rhythm.

Importantly, this transition is not driven by desire alone.

Urbanization compresses time. Climate volatility compresses choice. Meanwhile, Climate and Traditional Food Transition unfolds as industrial processing stretches shelf life while flattening nutritional range. As a result, diets drift toward energy-dense foods that ask less of land, labor, and memory—but also return less in micronutrients, fiber, and ecological connection.

The body adapts, for a while.

Hidden hunger grows where fullness persists. Iron, zinc, and diverse plant compounds quietly diminish, even as calories remain steady. Moreover, taste itself changes. Palates adjust to sugar, salt, and refined textures, while older flavors—bitter leaves, coarse grains, slow ferments—fade from daily life.

This is not a collapse.

It is a smoothing.

And smoothing favors sameness.

As the nutrition transition deepens, biodiversity slips further from the plate. Fewer species feed more people. Fewer varieties carry the weight of survival. Eventually, food begins to resemble infrastructure—functional, efficient, and emotionally distant.

Still, the transition does not erase tradition everywhere at once.

In some kitchens, diversity holds on at the margins. In others, it returns during festivals, illness, or memory. Yet the overall direction remains clear: as food systems scale for speed and certainty, dietary diversity becomes harder to sustain.

Therefore, the nutrition transition is not simply a health story.

It is an ecological story told through appetite.

And it prepares the ground for the next pressure—

where markets, climate, and biodiversity intersect most sharply.

4. Biodiversity as the Hidden Grammar of Food

Every language has rules that speakers follow without naming.

Food does too.

Biodiversity is that grammar.

It decides which crops stand together in a field, which flavors arrive together on a plate, and which nutrients quietly complete each other in the body. Long before nutrition learned to count, diversity learned to balance. Therefore, what looks like abundance in traditional diets is often structure—patterns refined through repetition, loss, and repair.

In diverse food systems, no single crop carries the whole sentence. Instead, meaning emerges through combination. Grains speak with pulses. Greens soften roots. Fermented foods interrupt spoilage and steady digestion. Consequently, nourishment becomes relational rather than singular. Health does not sit in one food, but in the way foods answer each other.

This is why biodiversity matters beyond conservation.

When many species and varieties remain in circulation, food systems retain flexibility. If one crop fails, another steps forward. If one season shifts, another pathway opens. Likewise, diets anchored in diversity adapt more easily to stress—nutritional stress, climatic stress, and cultural stress. The grammar holds even when words change.

However, when biodiversity thins, grammar collapses.

Fewer crops begin carrying more weight. Fewer varieties repeat across landscapes. As a result, meals simplify not because simplicity is desired, but because alternatives disappear. Over time, the plate loses punctuation. Everything begins to read the same.

This is where Climate and Traditional Food Transition tightens its grip.

Climate pressure narrows what grows reliably. Markets narrow what circulates efficiently. Together, they compress biodiversity at every level—genetic, species, and dietary. What remains may still feed populations, but it speaks a reduced language. Calories survive; complexity struggles.

Yet biodiversity does not vanish completely.

It retreats.

Yet it survives in home gardens, in mixed fields, in marginal lands, and in memory.

It persists where people still plant more than one thing because experience says the sky cannot be trusted.

And it lingers in foods that do not travel well but endure locally. Thus, biodiversity continues to function as grammar—even when it is spoken softly.

Importantly, this grammar shapes not only nutrition, but resilience.

Diverse food systems buffer uncertainty. They absorb shocks unevenly rather than collapsing uniformly. They distribute risk across crops, seasons, and practices. Therefore, biodiversity does not merely decorate diets; it stabilizes them. It allows food systems to bend without losing coherence.

Seen this way, biodiversity is not an external value added to food.

It is the structure that makes food intelligible in the first place.

When that structure weakens, diets lose fluency.

When it holds, tradition remains readable—even under pressure.

The next climb will take us where this grammar is tested most sharply:

at the intersection of climate strain, market speed, and ancestral pathways.

5. Climate and the Strain on Ancestral Food Pathways

Ancestral food systems do not disappear suddenly.

They thin.

They stretch.

And they begin to cost more than before.

For generations, these pathways—seed to soil, soil to kitchen, kitchen to memory—operated within a climate that, while never gentle, was at least familiar. Seasons argued, but they returned. Rains misbehaved, but not endlessly. Within that rhythm, tradition learned when to wait and when to act.

Now, however, the rhythm hesitates.

Climate pressure does not attack tradition head-on. Instead, it applies strain at every joint. Planting dates drift. Harvest windows shorten. Storage practices falter under heat and humidity that no longer behave as expected. As a result, foods that once fit neatly into seasonal cycles begin slipping out of alignment.

This is where ancestral pathways feel the weight most sharply.

Traditional crops often rely on precise timing—short rains, long dry spells, cool nights, predictable floods. When those signals blur, the logic that held certain foods in place weakens. Consequently, farmers begin adjusting not because they want to abandon tradition, but because the ground no longer offers the same answers.

Adaptation follows necessity.

Some crops are replaced with faster-growing varieties. Others yield less reliably and are planted less often. Meanwhile, knowledge that depended on stable repetition—when to sow, when to ferment, when to store—becomes harder to pass down with confidence. Experience no longer guarantees outcome.

Thus, Climate and Traditional Food Transition presses hardest at the point where memory meets uncertainty.

Markets respond quickly to this strain. They favor crops that tolerate disruption, uniformity, and transport. In contrast, many traditional foods demand patience, care, and local attunement. Over time, the balance shifts. What once traveled short distances from field to pot now competes with foods engineered for long journeys.

Still, ancestral pathways do not vanish outright.

They fragment.

They persist in partial forms—reduced varieties, shortened practices, simplified dishes. A food once prepared in five steps survives in two. A grain once grown in many types remains in one. What endures is not the full system, but its outline.

This strain reveals something essential.

Traditional food systems were never static. They evolved constantly, shaped by droughts, floods, and scarcity long before modern disruption. However, the current pressure is different in speed and simultaneity. Climate stress now arrives layered with market acceleration, policy shifts, and nutritional narrowing. The strain multiplies.

Yet even under this weight, ancestral pathways still offer guidance.

They show how food systems once balanced uncertainty without collapsing into sameness. They remind us that resilience was built through diversity, not efficiency alone. And they suggest that adaptation does not require erasure—only careful reweaving.

The strain is real.

The ground is shifting.

What remains is the question of how much memory can be carried forward—

and what forms it may take as the climate continues to rearrange the path.

6. The Communities That Carry Memory in Their Hands

Memory does not survive in archives alone.

It survives in practice.

In many places, knowledge still moves hand to hand—quietly, without ceremony. A farmer chooses more than one seed because the sky no longer keeps promises. A cook adjusts a dish because the grain arrived earlier than expected. A parent teaches a child not only what to eat, but when—and why. These acts are small, yet they carry centuries.

Communities hold this memory not as doctrine, but as habit.

Indigenous and local food systems often preserve diversity through everyday decisions. Fields are mixed rather than singular. Home gardens stretch beyond convenience. Seasonal foods still arrive in sequence, even if the sequence now stumbles. Consequently, biodiversity remains present—not because it is named, but because it is used.

This is stewardship without spectacle.

Women, in particular, often stand at the center of this continuity. They save seeds, manage kitchens, remember which foods restore strength after illness, and which calm the body during heat or scarcity. Their labor rarely appears in policy language. Yet it anchors resilience where formal systems fail to reach.

Still, the burden grows.

As climate strain intensifies and markets accelerate, holding memory demands more effort. Time compresses. Inputs become costly. Younger generations move away from land-based rhythms. Knowledge that once passed naturally now requires intention. Therefore, continuity becomes an act of choice, not default.

And yet, memory persists.

It persists in shared meals that still follow seasons.

It persists in community exchanges of seeds and foods that do not appear in markets.

And it persists where people refuse to rely on a single crop or a single source of nourishment. Even under pressure, diversity remains a quiet strategy.

Importantly, these communities do not claim perfection.

Within Climate and Traditional Food Transition, they adapt, improvise, and sometimes let go. What matters is not purity, but responsiveness. Tradition survives not because it resists change, but because it knows how to bend without breaking. In this way, cultural knowledge behaves much like biodiversity itself—distributed, redundant, resilient.

Within this broader Climate and Traditional Food Transition, these communities function as living archives.

They do not offer solutions in the abstract. They demonstrate alignment in motion. Their practices show how food systems once absorbed uncertainty without collapsing into uniformity. They remind us that resilience is built locally, even when pressures arrive globally.

The future does not depend on preserving every practice unchanged.

It depends on keeping the capacity to adapt without forgetting.

Memory carried in hands is fragile.

But when it moves across many hands, it endures.

7. The Slow Rebirth: Adaptation Rooted in Old Wisdom

Rebirth, when it comes, rarely announces itself.

It does not arrive as solution or promise.

Instead, it moves slowly—through adjustments that look ordinary until time reveals their shape.

In many places, adaptation begins by returning to what once worked, not by copying it, but by listening to why it worked. Farmers reintroduce mixed cropping where single harvests fail too easily. Households revive grains that tolerate heat and irregular rain. Gardens stretch again beyond convenience, because diversity proves more forgiving than precision.

This is not reversal.

It is reweaving.

Within Climate and Traditional Food Transition, adaptation rooted in old wisdom does not reject modernity. It filters it. New tools enter where they help; old practices remain where they still answer the land. The goal is not purity, but balance—between speed and patience, yield and resilience, scale and locality.

Seeds play a quiet role here.

Climate-resilient landraces resurface not as relics, but as options. Crops once considered minor regain relevance because they endure stress without demanding excess inputs. These plants carry histories of drought, flood, and poor soil—histories that feel newly contemporary. Thus, the past offers traits the present suddenly needs.

Equally important are the practices surrounding food.

Fermentation returns where storage becomes uncertain. Seasonal eating regains logic where transport grows fragile. Shared knowledge—when to plant, how to combine foods, how to recover soil—circulates again, sometimes informally, sometimes through renewed community spaces. Adaptation unfolds less through instruction and more through exchange.

This slow rebirth does not aim for abundance as spectacle.

It aims for continuity.

What survives is not the full architecture of tradition, but its reasoning. The understanding that food systems remain strongest when they distribute risk, honor diversity, and stay responsive to place. In this sense, adaptation is not invention; it is memory applied forward.

Still, the rebirth remains uneven.

Not all knowledge returns. Not all pathways reopen. Climate pressure continues, markets continue, and simplification remains tempting. Yet even partial restoration matters. Each regained crop, each revived practice, widens the margin for resilience.

The future, then, does not lie in choosing between old and new.

It lies in alignment.

Alignment between what the land can still offer and what food systems ask of it.

Alignment between human need and ecological limit.

An alignment that accepts uncertainty without surrendering diversity.

The rebirth is slow because it must be.

Anything faster would forget too much.

And so the story approaches its final bend—not toward conclusion, but toward reflection—where voices enter not to explain, but to sit with what has been carried this far.

8. Seeds of Change — A Reflection Before the Characters Enter

Change rarely begins where attention points.

It begins where habits loosen.

Seeds of change do not announce themselves as solutions. They sit quietly inside fields that are replanted with hesitation, inside kitchens where one old grain returns beside a newer one, inside hands that pause before discarding what once sustained them. These seeds do not promise restoration. They offer direction.

By now, the pattern is visible.

Climate has pressed on food systems without waiting for permission. Traditional pathways have strained, adapted, thinned, and sometimes held. Biodiversity has retreated in places, persisted in others, and reappeared where memory remained active. The nutrition transition has moved steadily—not as a moral failure, but as a consequence of pressure meeting speed.

Yet within that movement, something resists collapse.

Not loudly.

Not uniformly.

Resistance appears as choice made smaller, slower, more attentive. It appears where diversity is kept not because it is celebrated, but because it works. It appears where people notice that alignment matters more than control, and that continuity matters more than scale.

These are not revolutions.

They are adjustments.

Seeds of change grow best in such conditions—when certainty fades, but care remains. They do not belong to the future alone. They are already present, embedded in practices that never fully disappeared. What changes is not their existence, but our ability to recognize them.

This is the quiet threshold.

Beyond it, the story no longer belongs only to fields, markets, or systems. It moves into conversation—into how people sit with these changes, question them, and carry them forward without forcing resolution.

Before voices enter, it is enough to notice this:

The land has not stopped responding.

Neither have those who still listen.

And so we pause here—not to conclude, but to make space.

The table is being set.

🍂 Hello, Artista

Artista:

I keep thinking about something you said earlier—that food forgets before people do. Is that really true?

Organum:

Often, yes. Plates change faster than memories. And memories change faster than language admits.

Artista:

That feels unsettling. As if we are eating futures we haven’t named yet.

Organum:

Or pasts we no longer recognize. Sometimes both.

They sit for a moment, the table between them holding a meal that looks ordinary enough. Nothing ceremonial. Nothing dramatic. Yet something about it feels carefully chosen—grains that take longer to cook, greens that carry a bitterness not everyone likes, a texture that asks for patience.

Artista:

When I was young, certain foods arrived only in certain months. We waited for them. Now everything is always available, but it feels thinner somehow.

Organum:

Availability can hollow things out. When seasons lose their edges, meaning softens too.

Artista:

So this transition we’ve been circling—this Climate and Traditional Food Transition—it isn’t just nutritional, is it?

Organum:

No. It’s temporal. It rearranges how we experience time. What we wait for.

What we rush toward.

And what we abandon because it no longer fits the speed of the world.

Artista traces a finger along the rim of the bowl, thinking.

Artista:

Do you think we can return?

Organum:

Return is the wrong word. Nothing returns untouched. But alignment—that still happens. Quietly. In choices that look small enough to ignore.

Artista:

Like keeping one old grain in the pantry?

Organum:

Like cooking it often enough that it remembers you.

They smile—not because the problem feels solved, but because the conversation feels honest.

Outside, the day continues with its own arrangements. Inside, the table holds steady for now. Not as resistance, not as nostalgia—but as a moment of attention.

Artista:

Maybe that’s all we’re really asked to do.

Organum:

Perhaps. Notice what still responds. And care for it without asking it to save us.

The food cools slightly.

The room stays quiet.

And somewhere beyond the walls, fields continue their long negotiation with the sky.

✍️ Author’s Reflection

I did not begin this piece with answers. I began it with attention.

The land led first. Then the table. Then the small habits that rarely announce themselves as history. Along the way, climate appeared not as an enemy to argue with, nor as a force to worship, but as a presence that rearranges conditions faster than language can respond. Food followed. Memory followed later.

I wrote this not to settle debates, but to sit with a pattern I could no longer ignore within Climate and Traditional Food Transition: that change often enters our lives materially before it enters our understanding. Fields adjust. Crops narrow. Diets reorganize. Only afterward do we begin asking what happened.

This reflection does not claim innocence for humanity, nor guilt for nature. Catastrophe is older than us. Yet so is care. What remains within our reach—how we treat soil, water, seeds, air, and the chemicals we release into shared spaces—still matters, not because it will save the planet, but because it will shape the lives that come after ours.

I was not alone when I wrote this. Others spoke, and I listened.

Some voices came from reports and studies. Others came from kitchens, seed jars, and remembered seasons. Still others arrived quietly, as questions that refused to leave. I tried to let them stand without forcing them into conclusions.

If this article offers anything, it is not instruction. It is alignment—a reminder that attention itself is a form of responsibility, and that continuity often survives not through grand fixes, but through small, repeated acts that stay close to place.

Somewhere beyond these words, fields are still negotiating with the sky.

So are we.

And perhaps that is enough, for now.

🌼 Articles You May Like

From metal minds to stardust thoughts—more journeys await:

- The Geometry Principle: From Cosmic Harmony to Human Thought

The Geometry Principle: cosmic harmony shaping nature, art, and ethics—from constellations and shells to sundials and clocks. - Agriculture and River Health: A Tale of Zarvan’s Water Journey

Agriculture and river health entwine in Zarvan’s tale—rivers wounded by farming, yet carrying hope of balance through nature’s wisdom.

Curated with stardust by Organum & Artista, under a sky full of questions.

📚 Principal Sources

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2013). Biodiversity and nutrition: A common path. FAO.

https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/food_composition/documents/upload/Interodocumento.pdf - Ambikapathi, R., Fanzo, J. C., Schneider, K. R., Davis, B., & Herrero, M. (2022). Global food systems transitions have enabled affordable diets but had less favourable outcomes for nutrition, environmental health, inclusion and equity. Nature Food, 3, 764–779.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-022-00588-7 - World Health Organization, & Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. (2015). Connecting global priorities: Biodiversity and human health – A state of knowledge review. World Health Organization.

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241508537 - Nutrition for Growth. (2025). Recommendations for developing commitments on transition towards resilient and sustainable food systems for nutrition. Nutrition for Growth Paris 2025.

https://nutritionforgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/2-Transition-Food-Systems-final.pdf

Relevant chapters and sections were interpreted through a narrative lens rather than cited academically.

This article is also archived for open access on Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17953212

Leave a Reply